White (

Tuber magnatum) and black (

Tuber melanosporum) truffles.

Truffles. Tartufi. What are they? Chocolates? Tubers, like their names? Mushrooms? An acquired taste? Why so expensive? A million questions, many appetites, much interest. And so it transpired two Saturdays ago that 22 of us jumped out of bed at some breathtaking hour of the morning and piled onto a bus, on the

trail of the truffles.

An hour or two later, we disembarked in

Savigno, scene of the annual

truffle festival in November which I'd taken in soon after arrival in Italy, and where they take their truffles very seriously, as you might expect of a town whose population is 2000, about 200 of whom are truffle hunters.

We loitered in town for a while before heading to the forest, and had the good fortune to get a tour of the basement of

La Bottega del Macellaio, a 110-year-old family business. We dodged the hams curing in the rafters to see some cured

lardo which we'd heard about in our cured meats lectures; it was among the first cured meats to find protection under the

Arca del Gusto, (Ark of Taste), a project of Slow Food which seeks to protect traditional food products. After at least six months of seasoning and curing it's served in thin slices like any other meat product, eaten on hot toast.

Lots of lardo

On we went. This has been a bad year for truffles, apparently: not enough rain, and ongoing and growing problem with too many hunters, too many inexperienced dogs, and poor forest management.

Forests in Italy mean hunters of many kinds, but we were, hopefully, not going to meet the kind with guns in this one.

We were looking for

Tuber magnatum, the white truffle, found mostly in northern and central Italy and also known as the

Alba truffle, because the enterprising citizens of Alba thought to nab the trademark while they could, though it's not found only there. There are other varieties in these woods as well, like

Tuber melanosporum - the black truffle. Although their Latin name is Tuber, they are not tubers, vegetables like potatoes for example. They are uncultivable fungi, a symbiotic variety: they exchange mineral salts with tree sugars, which is why they are always found in the roots, or near them, of trees.

We met two kinds of truffle dogs too. The first, the

Lagotto Romagnolo, resembles a poodle and is the star among truffle dogs.

Pupa the dog and Adriano the truffle hunter.

The second,

Hungarian Vizla, is a short-haired hunting dog, and we had the chance to witness some truffle training of a very high spirited four-month old.

Rosita and Stella.

Both our hunters used only female dogs, and this is apparently quite common. I'd heard that pigs were sometimes used for truffle hunting, but they apparently make a terrible mess - truffle hunting is a game of stealth and concealment, and any truffle-beds must be returned to a pristine state so that the truffles may re-grow there and other hunters not see the location.

One of the tools used to dig truffles. The hunters carry long-handled short-bladed truffle spades, which double as walking sticks, and carry the

sapin, a hand tool used to pry the truffle out of hiding.

Black winter truffle.

After the truffle hunt we stopped for lunch and a tour of an old flour mill,

Il Mulino del Dottore, where we watched water-powered stone grinding of grain. They grind corn, wheat and chestnuts there, and the shop seemed to get a steady stream of local business. Our venue for supper,

Da Amerigo, gets the flours for its pasta from this mill, which has been in operation since 1680.

The cross on the roof of the mill, surmounting the crow which was the family emblem, advised pilgrims crossing the Appenines that they could find food and lodging here.

We had a talk about truffles by longtime truffle merchant Luigi Dattilo at

Appennino Funghi e Tartufi. He talked about the products - truffle oil, rice, pasta, polenta and pasta sauces flavoured with truffles - and then we watched a truffle dealer handle the merchandise - staggering to consider the monetary value of what we were observing.

He chooses them by smell, feel, weight and appearance. Because his customers may shave them at the table they need to look nice. He says that a partially-nibbled truffle is not necessarily a reject, since it says something found this one good enough to eat!

It was getting late but we found the time to taste some local wine at

Vigneto San Vito and pick up a few bottles for our supper.

We then braced ourselves for a five course meal of truffles and seasonal goodies at

Da Amerigo. Much loved by the Slow Food people, it's described in the famed

Osterie & Locande D'Italia guide as "a perfect combination of innovation and tradition." Which I think we agreed with the moment the first course landed on our table.

It was a soft, warm polenta served in parfait glasses, its surface layered with shaved white truffles which we stirred into the mixture to eat -- after first enjoying the perfume. Beautiful.

Swiftly followed by Parmesan gelato: parmigiano-reggiano cooked with cream, formed into gelato-sized balls, drizzled with some fine balsamico and served on a wee local flatbread. To die for.

Third starter - chicken and veal lasagne with black truffle shavings.

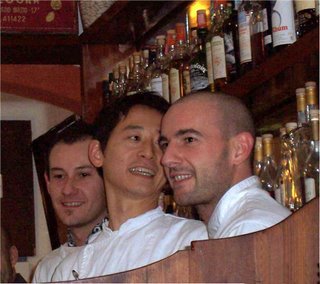

Mmmm... so happy...

Main course - lots of lovely chili-tossed vegetables and nuggets of fresh local pork, girded in pancetta and crowned with frizzled cabbage.

Dessert was a mercifully dainty, delicate and delicious gelato trio: pumpkin (

zucca) topped with some orange

marmelata, pomegranate (

melograno) and

persimmon (

cachi).

Praise to the chefs.

Labels: truffles